Winter Sprinting Alternatives

The climate of upstate New York has a little bit of everything. Summers on the lake, winters on the slopes, and the transitional 60 degrees of the spring and fall. For those of us trying to increase speed, the winter months can prove challenging in finding adequate space to open it up and do some serious sprint work. But, fear not! There are alternatives to developing and maintaining speed in these indoor-centric days. The following can help you get faster even when the weather isn’t syncing up with your speed goals.

Winter: great for skiing, not for sprinting

Mechanics Work

Running is both breathtakingly simple and mindbogglingly complicated. With the improvements in sports science technology allowing for even more in depth analysis, this is an exciting time for running aficionados. However, some of the big brains out there (PHDs and sports scientists in labs) still can’t seem to agree if vertical forces or horizontal forces are more important in human locomotion. I am a mere practitioner in this realm and lack the lab coat background necessary to get caught up in that battle. But, I have some practical experience that can help you clean your technique up and make your running movement more efficient.

We can break sprinting down into two basic components: the knee drive and the paw back. They are the cyclical yin and yang in running, and both can be improved with proper training. All you need is a set of active cords (or some rubber tubing variation), and a little bio-mechanics background and you are ready to go. I use active cords on a daily basis in our speed classes, and believe they should be as big a part of an athlete’s physical prep as a barbell is.

Jumping

Jumping metrics are huge in profiling athletes. There isn’t a professional sports franchise in the world that doesn’t look at different jumping numbers in analyzing prospective draftees. The gold standards are generally a broad jump variation (2 leg, 1 leg), and a vertical jump variation (2, 1, standing, running). While the jumping numbers don’t tell EVERYTHING about an athlete, they sure tell a good amount.

Jumping numbers can be used as a fatigue/over-training indicator. If jump numbers are down, it might be time to focus more on recovery. Jumps can be analyzed on a Bosco Jump Mat to determine different reactive qualities (ask my buddy Jeff Moyer more about this). But primarily, jumps are used to see what kind of force an athlete can generate to fling their body through the cosmos. The better the push with the jump, the better the athlete can get up and out.

I have seen and recorded hundreds of high school and college athletes throughout my years in this profession. I have yet to see an athlete I’d consider “fast” with less than a 7 foot broad jump or a 20 inch vertical jump. Their run technique can be impeccable but if they lack the ability to put any real force into the ground, then they are like a Lamborghini with a 4 cylinder, all show and no go.

In the world of high level football there are 300 pound men that routinely broad jump over 10 feet and vertically jump over 30 inches. Scary, freaky, and true. For the high school athlete, a broad jump over 8 feet and a vertical in the mid 20s is usually enough to find your way on the field or court SOMEWHERE. And generally speaking, the bigger the athlete with those numbers, the more likely they are to secure a starting spot. After all, 250 pounds jumping 8 feet is more impressive than 150 pounds jumping 8 feet. Lastly, I have yet to see an athlete with a broad jump over 10 feet run a 5 second or more 40 yard dash. It just doesn’t compute. The athletes who jump better, run faster.

Acceleration

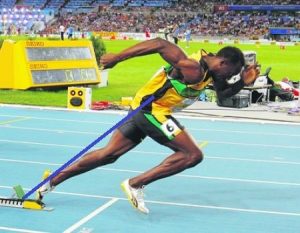

Arguably the most important feature of zipping around the field or court, an athlete who accelerates well can simply get to where they need to quicker and get themselves into position to do something awesome. Depending on the athlete, true top end speed gets tapped into anywhere from 40-60 meters. While that 40-60 mark is covered in some team sports, it is much more likely that shorter, quicker bursts will be the bread and butter of your athletic arsenal. All you need is a good 20 yard strip of real estate, your body, and a willingness to run as hard as you can. Throw in some video analysis and you can really get an understanding of how your body should drive away from the ground in an acceleration pattern.

Get there quickly and put yourself in a position to dominate

Olympic Lifts

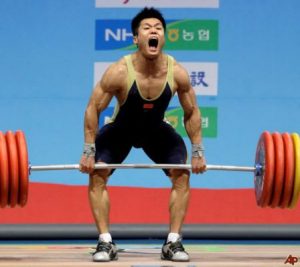

There is an ancient study from the catacombs of Soviet sports performance that featured Olympic lifters hanging with Olympic sprinters for the first 10-15 meters of a 100 meter dash. Several coaches have used this study as a reason for including Olympic lifts in their athletic programs. Unfortunately, finding this study isn’t the easiest task and my attempts were fruitless. But, rest assured it exists somewhere out there and has served as an anecdotal piece for including Olympic lifts in athletic programs for decades.

High level Olympic lifters are extremely impressive athletes

And why not? World Champion Olympic lifters usually have a tremendous blend of relative strength, mobility, and jumping abilities. All features that anyone attempting to get faster should strive for. However, we run into this pesky thing called context that muddies up the situation. The time spent perfecting this craft to achieve expert level is nothing short of legendary. These lifts are highly time intensive, with a steep learning and neuromuscular curve.

Most high school and college sport and strength coaches aren’t reviewing technique and slowly progressing the way it should be approached. And in their defense, why would they? What’s more important, knowing where to line up on the field or proper hip position on the first pull of a clean? Having both would be nice no doubt, but prioritizing what’s more important for that particular athlete’s sport usually takes precedent.

I think Olympic lifts are a tremendous way to make an athlete more powerful and explosive… if the athlete can do them well. If a kid really wants to learn Olympic lifts, has adequate physical characteristics to even attempt them, and is coachable then I think they’re a great option. But I’m also a realist and think that blanketing CLEANS FOR EVERYONE is setting certain athletes up for frustration, pain, and potential injury.

Velocity Based Training

Velocity Based Training (VBT) is becoming more of an en vogue method in athletic performance circles. For the design of this article I won’t go into the ideas today. But, feel free to check out this video from Dr. Bryan Mann on some VBT principles.

Hopefully this winter is kind to us folks in the great northeast. If so, we can get outside and be flying around in no time. If not, these options can help tip the speed needle forward even when it feels like the beginning of The Empire Strikes Back outside.

Only Tauntauns sprinted on Hoth